I’ve seen yet another argument break out about what counts as “hard” SF. Some people think “hardness” is a yes or no property and are indignant if some work is excluded. So it’s time to go over the Mohs Scale of SF Hardness.

(For non-geologists, the Mohs scale is a way of rating the hardness of rocks. It ranges from talc (anything can scratch it) to diamond (no lesser rock can scratch it). For genre discussions this is, of course, a metaphor.)

Disclaimers up front: “Hardness” is a separate property from whether a story is entertaining, actually science fiction, part of a particular sub-genre, or possessing the Campbellian “sense of wonder.” Yes, there are stories that are diamond-hard without stirring any sense of wonder. Us Hard SF fans call them “boring.”

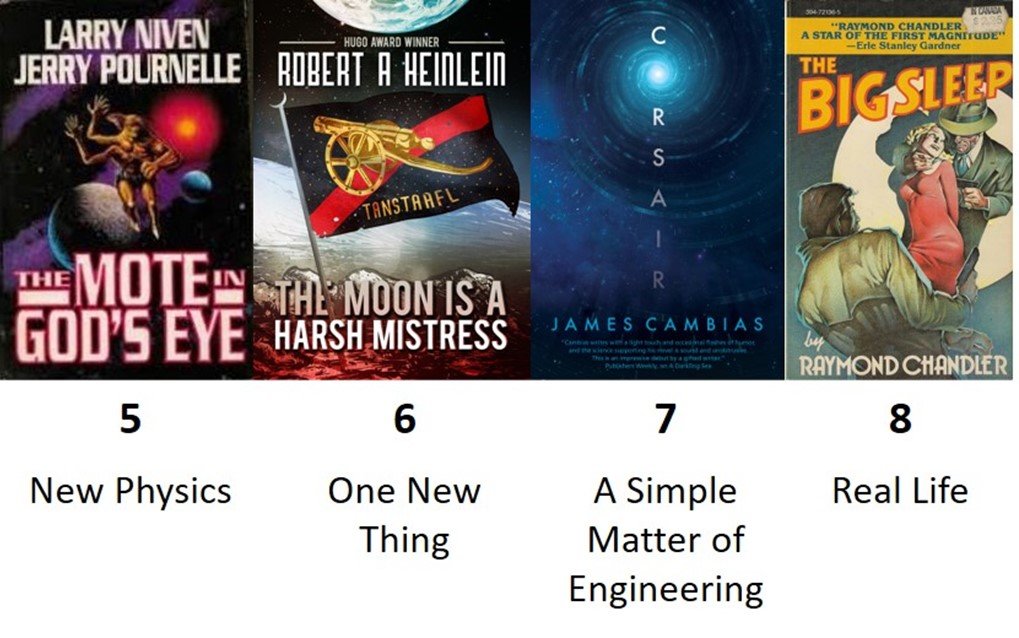

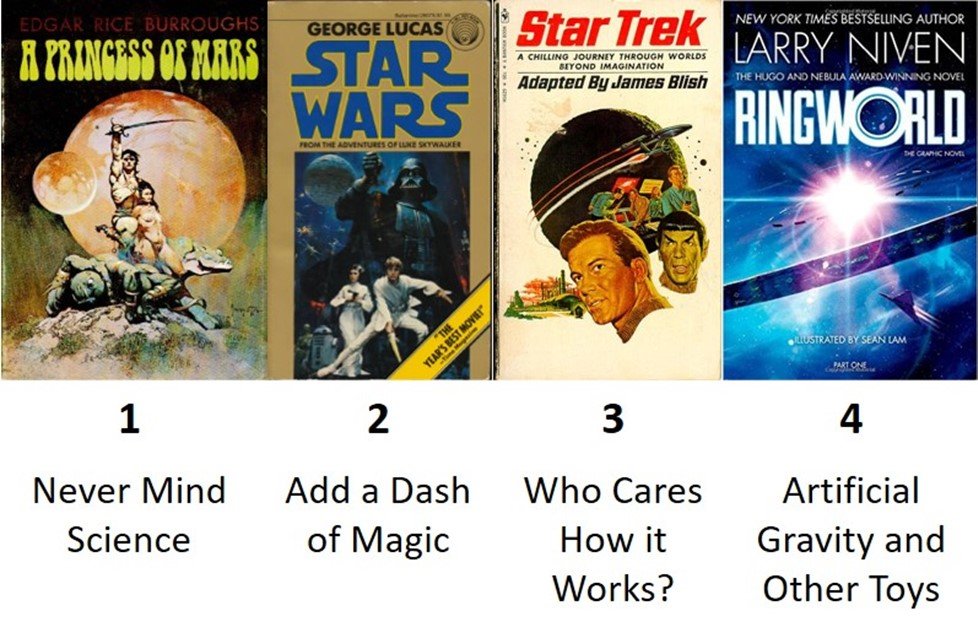

Eight: Starting at the hardest level of hardness, there’s Real Life. Everything in the story exists today. SF fans consider this the least interesting level. Pulp stories with hard-boiled detectives are here.

Seven: The next level is A Simple Matter of Engineering. The gadgets in the story are compliant with known science and could be built if we put in the effort. The settings are as realistic as current knowledge allows. The Martian is at this level with the exception of its initial dust storm. The ion drive of the Hermes and automated Martian fuel manufacturing landers are just awaiting funding. The recent discovery of permafrost in the Martian soil means the hero could have dug for his water instead of messing with hydrazine (shudder) but this doesn’t make the story less hard, it just dates it. James Cambias’ Corsair is here, and hasn’t been ruined by a new discovery yet.

One problem with this level of hardness is that it only makes sense a short distance into the future. If your story is set a thousand years from now it’s ludicrous to think there will be no new rules of physics discovered in that time. If the setting isn’t as different from today’s as our lives are different from the world of 1000 AD that’s a failure of imagination.

Six: The third level is One New Thing. Invent a gadget, scientific law, or strange place, and examine the implications as it interacts with known reality. Heinlein’s The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress is level seven with a spontaneously-created artificial intelligence. Niven’s “Inconstant Moon” is Real Life with an exploding sun. Corcoran’s Powers of the Earth adds an anti-gravity drive as its one thing, as AI and genetically engineered dogs have moved from speculative to a matter of engineering. My Torchship trilogy pushes the limits of this level with interstellar portals and a mass to energy converter.

Five: New Physics is where writers can invent lots of stuff. The trick to keeping it on this level is picking a few new inventions and dealing with their consequences rigorously. The Mote In God’s Eye and the related stories of Pournelle’s CoDominion series were here–Alderson drive, Langston Field shield, and weird yet plausible aliens.

Four: Artificial Gravity and Other Toys. Spaceships no longer need seat belts. This can still involve running numbers: Weber’s Honor Harrington series includes careful calculations of how much acceleration ships of each size can get from their gravitic impellers. This can still be “sense of wonder” hard SF. Ringworld had all sorts of impossible tech (teleporters, hyperdrive, invulnerable hulls, hereditary luck, and the scrith the Ringworld was made out of) but expanded our imaginations with what could be done with it. My Storm Between the Stars is at this level.

Three: Who Cares How it Works? Spaceships fly, blasters zap, Death Stars blow things up. The gadgets enable the heroes to do their stuff. Numbers are a distraction. Firefly and Star Trek fall here. Most space opera is here as well, such as Lee and Miller’s Liaden series.

One: Never Mind Science. Sometimes the author wants to do something and doesn’t care if it’s proven impossible. Mammals interbreed with egg-layers, rocks hang in the air, and Rule of Cool is all. (I understand some people are cranky about science forbidding mammal/bird cross-breeding, but that’s something our Neolithic ancestors understood, so it’s not cutting edge research.)

Too complicated? Oh, it gets worse. Many stories are rigorous in some areas of science and hand-wave others. An argument broke out over whether Dune was “Hard SF”. Where does it rank on this scale? The treatment of ecology is at One New Thing–a desert dominated by sandworms, with the implications for human society and future terraforming worked out in detail. Meanwhile the Bene Gesserit and Navigators Guild were effectively working by magic.

Another example of that mixed level is Bujold’s Vorkosigan series. Most tech in the stories is generic space opera, but the biological tech for reproduction, genetic engineering, and terraforming approach A Simple Matter of Engineering in the detail and accuracy provided. Whether this counts as “hard” SF depends on which aspect the viewer cares most about. If forced to assign a label I’d go with “partially hard” or “biologically hard,” which I’m sure amuses the twelve year olds in our midst.

So where is the line for defining something as “hard” SF? With most of the other things we argue about in the genre war it’s a matter of taste. I’ve noticed the most common line is artificial gravity. If the author make the crew strap in for acceleration and float the rest of the time the book will be called hard SF even if he’s resorting to blatant handwaves such as passing through a “loop of cosmic string” to travel between star systems.

This also points out the weaknesses in the definitions people are tossing around for “Campbellian SF.” Plenty of non-hard SF books such as Ringworld and Hogfather (a pure fantasy) provide the sense of wonder or “conceptual breakthrough” Campbellian fans desire.

The “hardness” of a story is just one way to describe it, separate from whether it includes any entertainment or other qualities. A hard SF story doesn’t guarantee it will provide sense of wonder. What the term “hard SF” does is give readers an idea of what to expect from the story, so they have a hint of whether it’s what they’re looking for. Which is all any genre label is really useful for.

FOOTNOTE: TVTropes has a version of this scale but I disagree with part of their analysis so I wrote this.

My problem with it is that Hal Clement had spaceships with FTL and translators he admitted were pure black boxes to him, and so ranks fairly soft.

Which is like saying that The Lord of the Rings is not a very good example of epic fantasy.

LikeLike

I’d say he’s like Bujold’s Vorkosigan series. In his case the planetary science was hard while he handwaved other parts of the tech. There’s a lot of “mixed” out there.

LikeLike

I realise that this is an occasional blog and as such you may not read responses very often, if at all. I like you Mohs hardness scale. As a science fiction writer I pitch myself at around 6. That “one new thing however” takes a lot of alternative physics to justify. My experience is that I have had to do several hundred hours of hard physics reading to rationalise why I “allow” that “one new thing”. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why I love the genre. Well done.

LikeLike

Thank you! Fortunately, the WP system notifies me of comments. The joy of the hard SF game is that you can get many times the original investment of time working out the implications of what can be done with the new thing, and hopefully some fun adventures for your readers (if not “fun” for protagonist).

LikeLike